Harmsen et al., 2026, Cell Metabolism 38, 65–81

January 6, 2026 © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Inc.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2025.11.006

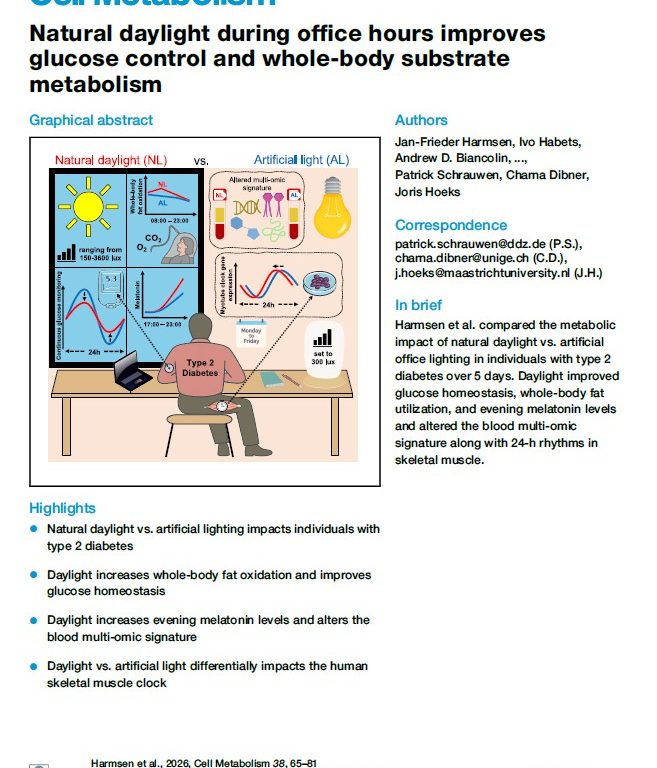

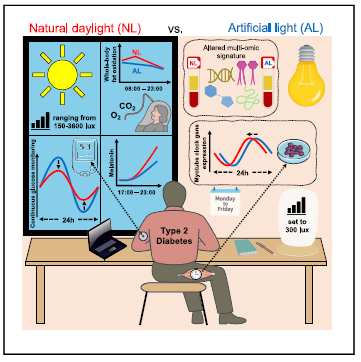

this image from the paper hiligts the study design and results.

The idea was compared the metabolic impact of natural daylight vs. artificial office lighting in individuals with type 2 diabetes over 5 days. “Daylight improved glucose homeostasis, whole-body fat utilization, and evening melatonin levels and altered the blood multi-omic signature along with 24-h rhythms in

skeletal muscle.

-Natural daylight vs. artificial lighting impacts individuals with type 2 diabetes

-Daylight vs. artificial light differentially impacts the human skeletal muscle clock

-Daylight increases whole-body fat oxidation and improves glucose homeostasis

-Daylight increases evening melatonin levels and alters the blood multi-omic signature” regarding Harmsen et al. hypothesis.

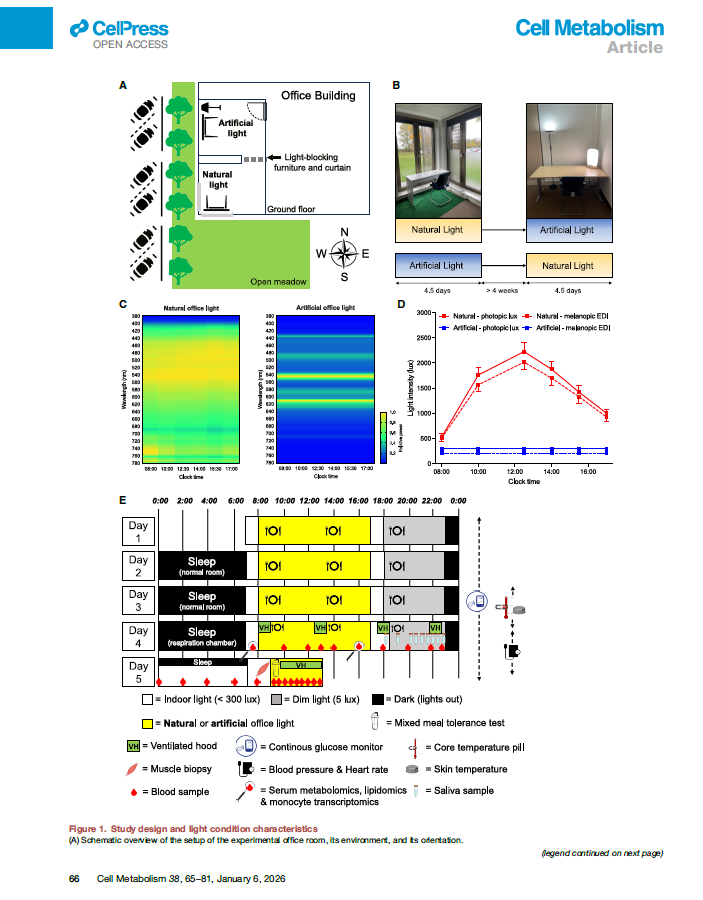

In order to isolate the causal effect of daytime light exposure on metabolic health and circadian regulation, 13 older adults with T2DM (metabolically stable and free of major acute comorbidities) were included in this randomized controlled crossover study. There were comparison: office environment with natural daylight exposure and office environment with artificial lighting, and for randomization, each participant served as their own control.

Harmsen et al., 2026, Cell Metabolism 38, 65–81 January 6, 2026 © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2025.11.006

Each experimental condition lasted 4.5 days and there were wash-out period between this 2 lighting intervention periods that lasts at least 4 weeks.

Following factors were standardised:

- Diet (caloric intake, macronutrient composition, meal timing)

- Physical activity

- Sleep–wake schedule

- Daily routine and room temperature

- Light intensity and spectral composition

Glucose control was performed via Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM)

- Continuous throughout each 4.5-day period

Energy metabilism via: Indirect calorimetry was performed

- At rest

- During metabolic testing sessions

- At predefined, standardized time points

With several ourcomes:

- Oxygen consumption (VO₂)

- Carbon dioxide production (VCO₂)

- Respiratory Exchange Ratio (RER)

- Relative fat vs carbohydrate oxidation

Measurements were not performed daily, but at fixed time points.

Also Mixed Meal Tolerance Test (MMTT) was performed once at the end of each 4.5-day experimental period to analyse:

- Postprandial glucose and insulin responses

- Substrate utilization following meal intake

Circadian Biomarkers were measured: Salivary melatonin profiling via everyday measurement in the evening (~18:00–23:00) at the end of each experimental perioud to assess circadian phase and entrainment

Percutaneous skeletal muscle biopsy were performed

- One to two biopsies per experimental period

- Performed at identical circadian time points

with several analyses

- Expression of circadian clock and metabolic genes

- qPCR and/or RNA sequencing

Additionally Multi-Omic Profiling were performed at the end of each experimental period, whereas samples were collected at standardized times of day

- Blood serum

- Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs)

- Metabolomics

- Lipidomics

- Transcriptomics

No subjective questionnaires were used

All conclusions are therefore based on objective physiological and molecular measures, not subjective sleep or psychological perception.

Conclusion

In this randomized controlled crossover study, exposure to natural daylight during office hours significantly improved metabolic and circadian outcomes compared with artificial lighting in adults with type 2 diabetes. Natural daylight increased time in the target glucose range, shifted whole-body metabolism toward greater fat oxidation (lower RER), and improved postprandial metabolic responses. Daylight exposure was also associated with higher evening melatonin levels, altered expression of circadian clock genes in skeletal muscle, and distinct systemic metabolic and lipidomic profiles, indicating improved circadian alignment and metabolic flexibility.

However, there were several limitations:

- Small sample size (n = 13)

- Short duration of exposure (4.5 days per condition)

- Highly controlled laboratory-like environment limits real-world generalizability

- Absence of subjective sleep and mental-health assessments

- No parallel group

What do you think? Should they continue?